CBC News: Two law professors at Dalhousie University say the school’s proposed process of verifying Indigenous heritage risks retraumatizing staff, students and faculty subjected to it, and could exclude those with legitimate claims.

Last year, the Halifax university created a task force to address how it should handle false claims of Indigenous identity.

It issued its final report in October, which found the lack of a consistent policy led to “conflict, disillusionment, and an erosion of trust” when people raise concerns about Indigenous identity fraud.

In December, the chair of the task force said the idea is not to police Indigenous identity, but to ensure non-Indigenous people aren’t taking advantage of resources and opportunities specifically meant for Indigenous people. Dalhousie says discussions are continuing on new rules which are not yet final.

Across Canada, there have been a few high-profile cases of Indigenous identity fraud in academia in recent years, including Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, who was once a tenured law professor at Dalhousie.

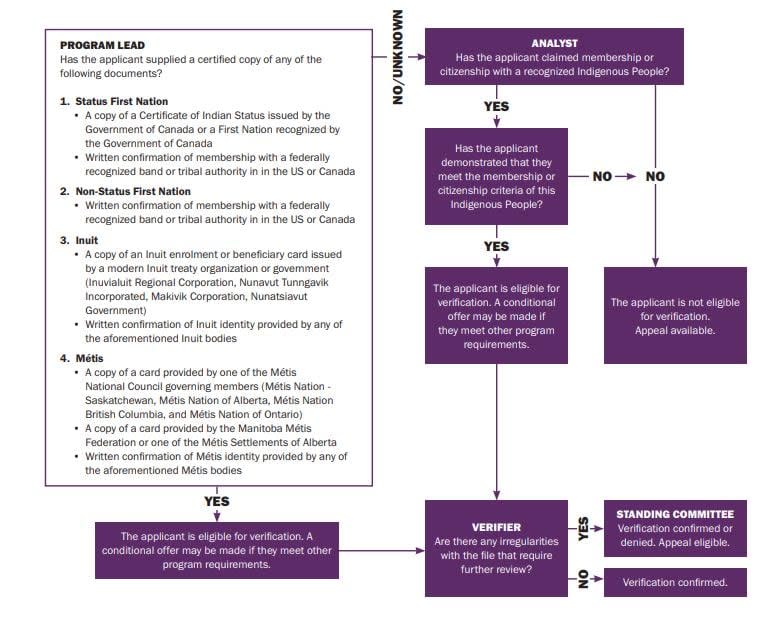

Dalhousie University outlines the proposed verification process in its Understanding Our Roots report, which was released in October. (Dalhousie University)

The school currently relies on self-identification of Indigenous heritage, but the task force is now recommending that people submit their federally issued status card or written confirmation of membership from a “federally recognized band or tribal authority” — similar to what the University of Saskatchewan implemented last year.

But Cheryl Simon of Epekwitk First Nation, an assistant professor at Dal’s Schulich School of Law, says this process could hurt staff, students and faculty who have legitimate and legally supported claims to Indigeneity.

“We have a lot of people that are scared,” Simon told CBC Radio’s Mainstreet Halifax last week.

“They are scared that ever since this report dropped in October that every single Indigenous person in Dalhousie is assumed to be fraudulent until proven Indigenous, and that is a really heavy burden to place on people that have suffered genocide.”

Last month, Simon co-authored a report with Naiomi Metallic of Listuguj Mi’qmaq First Nation, who is also a professor at the law school, that examined the legality of the proposed process through a human rights lens.

CBC News requested an interview with Dalhousie’s Provost Frank Harvey, but he declined. In an update posted to Dalhousie University’s website last month, Harvey said he has received valuable feedback from colleagues and more consultation is required.

“Developing the appropriate tools to support Dalhousie and Indigenous nations on this journey will require months of consultations at the local, regional, and national levels,” he wrote in the statement. “As we move forward, ongoing dialogue will be fundamentally important to ensure that all voices can be heard. We value all constructive feedback grounded in a strong commitment to nation-to-nation relationship-building.”

He also said there are no investigations of students, staff or faculty underway.

Relying on official documentation

In their report, Simon and Metallic take issue with the fact that the verification process relies on recognition under the federal government’s Indian Act — meaning the person has status — or official membership of a First Nation, or Inuit or Métis group.

“Case law does speak to Indigenous people being more than status Indian — that non-status Indians are recognized as Indigenous peoples and even people who don’t have federal recognition, potentially have legitimate claims,” Metallic told Mainstreet.

Cheryl Simon, an assistant professor at Dalhousie University’s Schulich School of Law, says the proposed process could hurt staff, students and faculty who have legitimate and legally supported claims to Indigeneity. (Dalhousie University)

She said this process may overlook several groups, including Indigenous people who are ineligible for Indian status because they are the result of two successive generations of mixed parenting, known as “parenting out,” or they belong to an Indigenous family from Newfoundland who was disregarded when the province was founded and “are still fighting for recognition.”

Metallic’s law firm, Burchell Wickwire Bryson LLP, represents NunatuKavut Community Council, a self-identified Indigenous group in south and central Labrador, but she told CBC she has never worked on the file.

Simon also takes issue with the process relying on federal definitions of Indigeneity, she told Mainstreet. “To have, in the name of reconciliation and nationhood, an institution take status and use it as proof of Indigeneity, it’s startling and this is why that continuation of colonialism comes to mind,” she said.

Documentation not always available

She said relying on documentation from the community can also create challenges for people who have fled due to domestic violence or other troubling reasons, or those who were adopted out when they were young don’t have any information about their Indigenous heritage.

“The reality of why so many Indigenous people are disconnected from the communities hasn’t been, I think, thoughtfully considered with this,” Simon said. “Because it assumes that home and community is a safe space. It assumes that it is set up to allow for those connections to be brought forward.”

She added that while the federal government documents Indigenous people, they don’t always do so adequately or accurately — which can cause a barrier even if people can return home. And sometimes the documentation no longer exists, Metallic said.

Naiomi Metallic, who is an associate professor at Dal’s Schulich School of Law, says sometimes you can’t know something with certainty. (Stephanie VanKampen)

Metallic said some people may suggest that that situation could be abused by people, but “sometimes you can’t know something with absolute certainty.” “In law, we don’t expect to even know anything with absolute certainty. We know we have the balance of probabilities — is that more likely than not?” she said.

“But it almost seems that in some of this discourse around fraud and — quote, unquote — pretendians, this search for absolute certainty really is just impossible.”

In their report, Simon and Metallic say the university already has the tools necessary to address situations of academic fraud of Indigenous identity, and no new process is necessary.

Author of report responds

Dr. Brent Young, the academic director for Indigenous Health at Dalhousie’s faculty of medicine, chaired the taskforce and was one of several authors of the report. He said he was surprised by the reaction of the two professors and thinks they misconstrued the report.

“My fear though with this type of dialogue that’s emerged, is that … people will not feel safe coming to the university and doing some of this work, if they are at risk of allegations coming out against them in the media, or rewriting of history of the work that they’ve [done],” Young told Mainstreet.

“And, so, I think that is damaging and that’s actually unfair and it’s not what we need right now.”

Young said the proposed process will evolve and the university is willing to work with Indigenous students, faculty and staff and their communities if they must prove their heritage.

Dr. Brent Young, who chaired the four-person taskforce, is the academic director for Indigenous Health in the faculty of medicine at Dalhousie University. (Danny Abriel/Dalhousie University) He said staff are already working with people applying to medical school, which has an admissions stream for Indigenous students.

“We worked with a student and we helped them get the information that they needed to be able to to build that case, like this is who I am and — done. This person is verified.”

Young said the university will continue to look to both federal regulations and Indigenous law when confirming heritage, while also working with nations. “It’s not as clear to be able to say is it over inclusive or under inclusive because there will always be colonial intrusion into the definitions of what it means to be Indigenous and that’s where we are today.

“It’s a very challenging area to navigate, but the key is that with any policy we don’t want to be creating more harm than the harm we are trying to address. And we can find common ground in all this if we actually allow the space to have safe dialogue, meaningful dialogue.”